Where have we come from?

The journey of personal mobile devices started in early 1980’s with first Motorola, Nokia and Ericsson phones. I would recommend looking up those funky handsets. They teach us a lot about ergonomics and evolution of microprocessors.

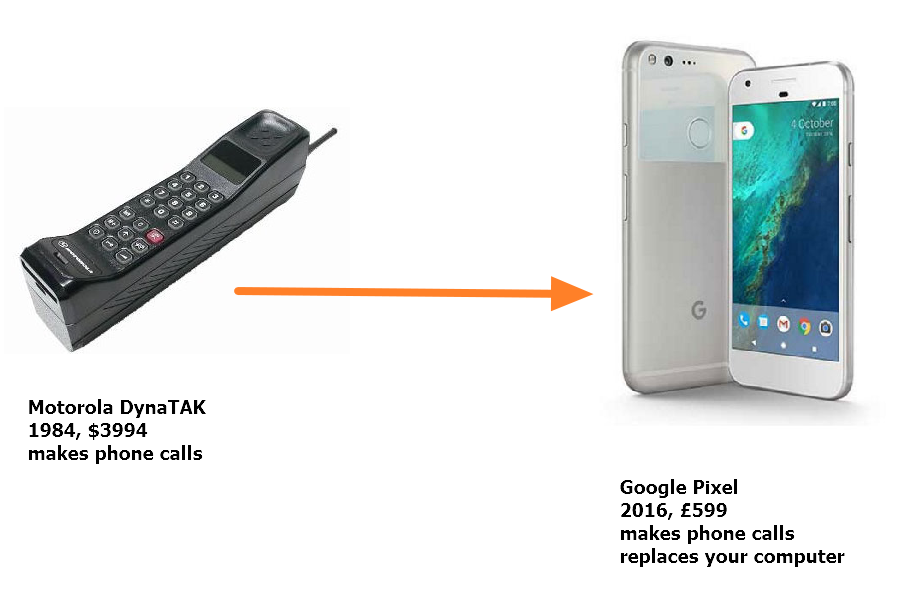

Basically, this is what our journey looks like:

Motorola DynaTak was first truly portable mobile phone for civilian use. It’s fortunately history by now and you may read more about it here.

Latest Android phone comes from Google, weighs no more than any other handset we have seen in past five years and replaces your computer. Other major OS’s are Apple iOS and Microsoft Windows 10 Mobile (somewhat dead in the water now). We had Blackberry OS, but that’s pretty much gone – all new handsets are running Android. We also had Symbian, but that’s completely irrelevant these days. Nokia is trying to reinvent its mobile business, though they seem to side more with Android than MeeGo. Although Nokia C1 is more of an urban legend – many rumours but no sighting yet…

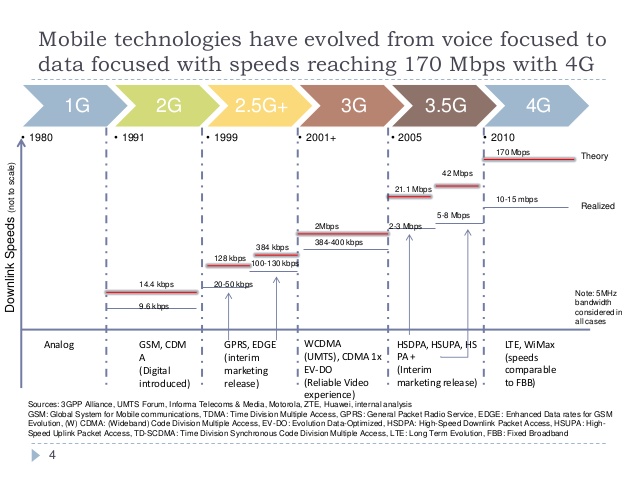

But none of it would have not happened without underlying infrastructure. Taking the risk of investing very large sums of money into covering has paid off and benefits manufacturers, service providers and consumers alike.

Signal coverage in the UK is relatively good with most areas having voice signal. 4G is confined to mostly urban areas but is growing faster than 3G.

4G standard has many advantages over its predecessors – data speed and improved voice quality. 4G connectivity has also helped many mobile virtual network operator (MVNO) companies to enter the market. There are ones that piggyback to major carriers for both voice and data or just data. In second option user would need to install and use an app to make and receive calls and send text messages. This option bypasses phone OS native apps and offers a few advantages to the provider – provide additional services and sell in-app advertising to keep package cost low.

Nokia, Ericsson and others have been hard at work developing 5G communications standard. Don’t expect that anytime soon near you as devices that support the standard are still not in personal but rather in machine-to-machine (M2M) and Internet-of-Things (IoT) market.

Where are we now?

It’s been an interesting journey people in most countries have been. In many places it has been led by technology rather than policy. And technology providers have been pushing their own (often proprietary) standards, which innovative at the beginning have caused countless hours of extra work to make it functional and integrate with other systems.

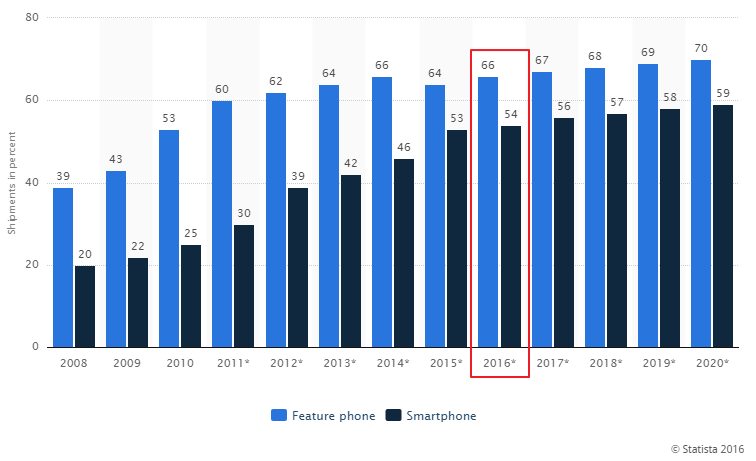

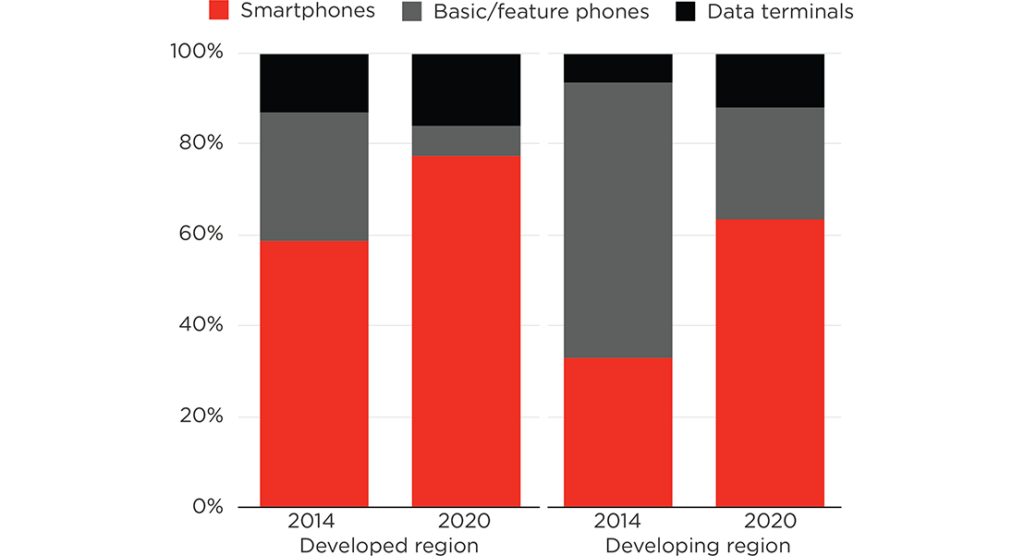

Most developed and developing countries have passed mobile phone revolution. Smartphones, however not taken over the mobile device market from feature phones yet, are on path to get there.

I don’t fully buy into Statista’s perception that feature phone numbers are on permanent raise. It’s likely though that what’s classified as a smartphone today won’t meet that designation in 2020. There’s another view that seems more likely, and that was view in early 2015.

My personal view is that feature phone numbers start dropping in next 24 months as African and Asian countries keep growing. Once a human being has had a taste of a smartphone they’d rather give up other goods and services than this. And why? Technically you have a small computer in your hand that puts world’s knowledge at your fingertips.

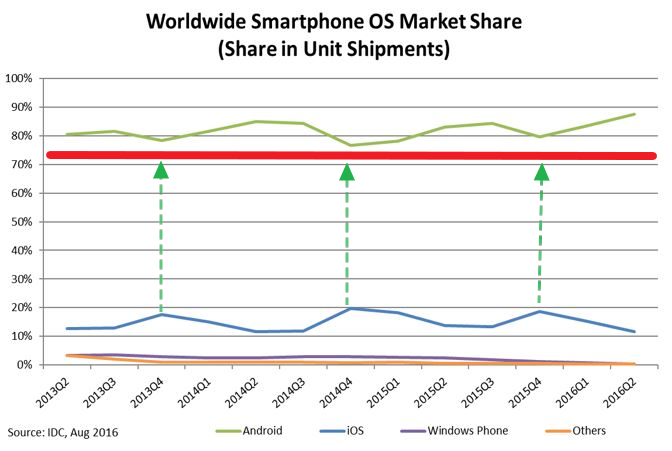

It’s not surprising that Android OS dominates the market. You can see interesting correlation between Android OS and Apple iOS. Every time Apple launches something new, there’s a surge and corresponding dip in shipments of Android devices. Yet it plateaus off very quickly and even takes a tumble after initial craze has faded. The gap between the market leader and second option is too vast to close at ease.

This dominance in turn gives Google enormous leverage over vast amounts of users. They are happy to share some insight with device manufacturers but all visible and hidden services of its client OS feeding information back to the company.

New gadgets, anyone?

Near Field Communication (NFC) has been on and off tech news. There are some services being adapted en masse now. Contactless bank cards? Check. Using your latest iPhone (or rather old Android and/or Blackberry) as bank card? Check. Having small contactless bank card companion chip (about square inch in size) attached to your old phone. Like this:

That’s now norm. But where to take this contactless future?

John Mclear was trying to get his NFC Ring off the ground using Kickstarter back in 2013. And what a marvelous idea it was! One ring, two functions – public and private. Public is the outer side of the ring, suitable for contactless payments and such. Inner side of the ring would be for authentication – as in handshake. No puns intended, though you could see two changing digital ID’s during physical handshake.

Then there are printable digital ID’s. These are the ones that can be tattooed or printed on the skin akin to 3D printing. Some films have featured characters with bar code tattooed to their bodies. That’s cool, but… what if your ID changes? Deliberately or not, but change is needed. What then? Well, you’d have to remove and replace old one. Rather painful exercise, I guess. Reprogramming embedded or printed NFC chip is not. And works perfectly so long as only certain authorities can do it. I’d rather travel without physical passport than with one.

Another example of this use – manufactured human spare parts. Ahem, organs and bones, that is. When I get into car accident and my leg gets crushed so badly that I need a new bone (provided that tissue is still usable) it should be crafted for me using suitable material and 3D printer. The cost of prosthesis manufacturing where and when it’s needed would go down radically and the only concern is how body reacts to it. Though manufacturing process would take into account personal characteristics minimising or removing potential negative effect completely.

What should we consider?

With masses of data being sensed, collected, analysed and presented we need to be aware of what we give away to improve our lives. It would be nice to provide 20% of input and reap 80% benefits but 80/20 rule doesn’t really work here. There are really two reasons for it.

First, most smartphone users have dozens of apps on their devices. We are actually really dependent on our devices. Where average amount has been limited to their niche time spent on using the mobile apps has doubled over five years.Those apps as mentioned in previous part collect behavioural information and pass it back to the service providers. he more time we spend on our devices the fuller picture app / service providers have about us.

Secondly, AI and analytics algorithms are improving but are not smart enough yet to provide the service at the cost of contact acquisition. It won’t take too long considering Google AI improvements in navigating London Underground. I can see these services powering the user analytics and being integrated into personal assistants.

What lies ahead?

What should we expect from the connected future? Is it good or bad, and should we be worried or happy?

There’s been an explosion of apps and services designed for smartphone users. Many are duplicating each other, many are using open data, some mash together open and personal data, some work with data providers and others allow user to enhance their experience by linking together services that make up our digital footprint.

We tend to trust our service providers. Or we don’t but compromise as a means of using a particular service. Take Google, Microsoft or Facebook as identity providers. Now add everything these companies know about you – that’s often rather a substantial digital footprint and you need to know what do with it.

There are always privacy concerns related “free” services. Data misuse is a big deal and major organisations have taken steps to deal wit it. Though it manifests itself a bit like this:

When a service is free at the point of delivery the consumer is the product.

The consumer needs to be aware of what information they give away about themselves, who they trust and what benefits they receive in return.

Google wants to be my personal assistant. So does Microsoft with Cortana, Apple with Siri and Amazon with Echo. And plethora of other services that are always listening using the gadgets we have amassed in our homes.

So with that in mind, how can I benefit from their knowledge about me?

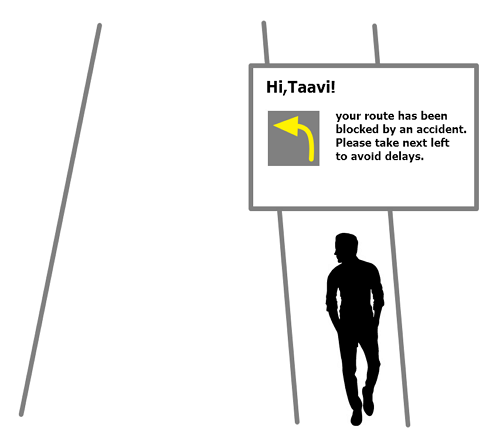

Consider a scenario when your city has been kitted out with connected interactive displays, let’s call them smart screen. Those smart screens are equipped with sensors and connected to each other. The devices we carry are technically beacons which also serve as ID providers. My smart watch is associated with one of my digital ID’s. The smart screen senses me approaching and gives me useful snippet.

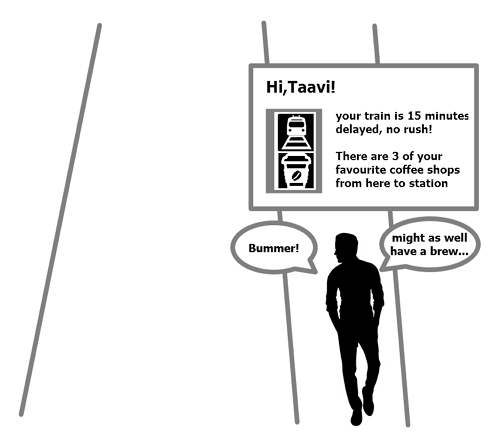

Or if I’m rushing to catch my train and smart screen tells me there’s a delay with my train and I’ve got to fill 15 minutes somehow.

Useful? Frightening? Amazing? Whatever we feel about these services penetrating our everyday lives they are here to stay for the foreseeable future. And they are not going to be less smart. They will reduce complexity at the point of delivery making it easier for the users to go about their daily lives and adding useful layer of information.

Should we be afraid of future or jump up and down of excitement when today’s tech news highlights become part of everyday life next week?

I think we should embrace the technology, work with it and reap benefits. When parts of it become too intrusive, we need to make conscious decision to stop using those parts. Not becoming Luddites but understand what is good and what is bad for us.

Back to the future!